How do you galvanize a community that has forgotten its heritage? As Adam Milstein realized 15 years ago, it takes passionate determination and tireless effort.

How do you galvanize a community that has forgotten its heritage? As Adam Milstein realized 15 years ago, it takes passionate determination and tireless effort.

Milstein emigrated from Israel with his wife and daughters in the early 1980s, became an American citizen in 1986, and built a thriving real estate development business. Around the year 2000, his daughters started dating young men who weren’t Jewish. He told his daughters he hoped they’d marry Jewish husbands. They asked him why.

Faced with this question from his daughters, Milstein realized he didn’t have an answer. As an Israeli, he’d spent his time in America sitting on his suitcase, always thinking he’d go back home. He’d sent his daughters to Jewish day schools, but faced with limited options, he’d sent them to a secular high school. Most of their friends were non-Jewish. They hadn’t formed deep bonds with the American Jewish community.

Milstein realized he hadn’t been sitting on a suitcase; he’d been sitting on a time bomb. He looked at Israelis like him in his community, realizing their identity as Israelis would be gone in one or two generations. He started by reconnecting with his culture on his own, attending Aish LA events and studying with Aish HaTorah Rabbi Dov Heller. Through these events, he found a new purpose: to transform his fellow Israeli-Americans into a community.

A Two-Pronged Approach

Milstein approaches his philanthropic efforts from two angles: conducting age-specific outreach and focusing on common interests. His goal was to reach second- and third-generation Israeli-Americans and through them, to reach their parents and grandparents.

Former Israeli-American Council (IAC) CEO Sagi Balasha, another Israeli-American, explains his generation’s thinking. “People come here with the intention to go back, and that creates a special psychology. You will not really try to be part of a Jewish community; you will not try too hard to integrate into American society; you will not spend your money on sending your kids to Jewish day schools because you’ll just speak Hebrew at home.”

Whereas American Jewish life centers around synagogues, Israelis rarely join these communities. Because they’re always ready to go home, they feel no need to assimilate into American Jewish culture, and they don’t want to pay to join the synagogues.

Milstein started reaching out to his community by founding the Sifriyat Pijama B’America. In keeping with his philosophy, it’s age specific, designed for 2- to 8-year-olds. It’s also built around a common interest, which is teaching children to read.

By the time children start gaining exposure to written Hebrew language through Sifriyat programs, they already have a strong oral base in English. If their Jewish parents speak Hebrew in the home, they also have an oral and aural command of Hebrew. These foundations make preschool the perfect time to start reading in both languages. Instead of reading “Goodnight Moon” one more time, Israeli-American parents receive free storybooks written in Hebrew.

By the time children start gaining exposure to written Hebrew language through Sifriyat programs, they already have a strong oral base in English. If their Jewish parents speak Hebrew in the home, they also have an oral and aural command of Hebrew. These foundations make preschool the perfect time to start reading in both languages. Instead of reading “Goodnight Moon” one more time, Israeli-American parents receive free storybooks written in Hebrew.

Milstein also started with the Sifriyat program for another strategic reason. In addition to building a foundation on Hebrew language, these storybooks stir strong feelings of nostalgia for parents. The stories are the same stories they read when they were children growing up in Israel. The books begin to stir connections to their culture, building a desire for what they’ve lost.

Why Hebrew Matters

Americans tend to view learning a foreign language in terms of either utility or cultural literacy. American businesspeople learn Chinese to gain a foothold in the global marketplace, or healthcare workers learn Spanish to speak to patients in their communities. Also, learning a foreign language has always been a pillar of a classical liberal arts education. Unfortunately, few Americans who take second-language classes put their new skills into practice.

For the Jewish community, the Hebrew language has a much deeper meaning, especially for Israeli-Americans. While nearly seven in 10 American Jews practice Judaism, many Israeli-Americans live secular lives. The Hebrew language becomes a way of reconnecting to Jewish roots among a community in which faith is less relevant. By exposing children to Hebrew through stories they enjoy, learning Hebrew becomes a joy, not a parental directive.

Based on the success of Sifriyat, Adam Milstein expanded his outreach to Israeli-Americans in other age groups. He created programs that connected elementary school students, through online lessons and video conferencing, to Hebrew language teachers in Israel. Milstein also supports Friends of Israel Scouts, which is an American version of Tzofim, an Israeli program with some similarities to the Boy Scouts of America. The program has four Schvatim, or tribes in Southern California, and programs are conducted in Hebrew. Students learn about Israel and, after graduating from high school, have an opportunity to spend a gap year in Israel.

On College Campuses

College campuses tend to be a place where herd mentality reigns. Students gravitate toward labels instead of thinking deeply about the movements they join. On campuses, BDS sentiments have gained a foothold by aligning with progressive causes, like LGBT equality and environmental preservation. Students sometimes adopt anti-Israel sentiments without thinking deeply about anti-Semitism.

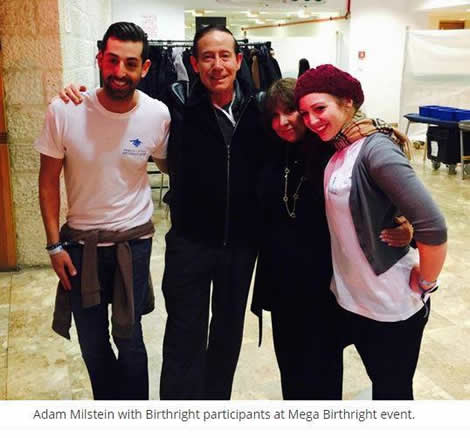

The Milstein Family Foundation, through the IAC, is a foundational supporter of the Taglit-Birthright Israel program. Taglit-Birthright sends young adults, ages 18 to 26, who have at least one Israeli parent, to visit the state of Israel. On these trips, young adults explore their heritage and over 3,000 years of Jewish history.

When asked why Birthright trips were limited to Israeli-Americans, Milstein said, “When an Israeli-American comes on Birthright, the impact is probably five times more than the impact on Jewish-Americans. The reason is simple — Israeli-Americans are connected to Israel already.” Even Israeli-Americans who’ve visited family back in Israel don’t necessarily know the land of Israel. “They know the house of their grandma,” says Milstein. “They know the beach in Netanya.”

In addition to funding trips to the homeland, the Milstein Family Foundation sponsors groups like Mishelanu, which gives Israeli-Americans a home away from home on college campuses. The Milsteins also support Hillel, Alpha Epsilon Pi, and the Merona Campus Leadership Foundation.

Networks for Young Professionals

After graduating from college, Israeli-American young adults find themselves where Milstein’s daughters were 15 years ago. They’re thinking about building careers and starting their families, and it’s tempting to drift away from Jewish culture.

Although it’s not clear which causes the other, there’s a clear correlation between lack of religiosity and intermarriage. According to Pew, 79 percent of Jews who are non-religious have a spouse who isn’t Jewish. In intermarried families, one-third of parents raise their children without any introduction to Jewish faith.

To give Israeli-American young adults the chance to meet other young Jewish professionals, Milstein encourages participation in programs like B’Nai B’Rith. It’s a young professionals network designed to build community among working Israeli-Americans and American Jews ages 12 to 40. Milstein is practical; he understands that after three or four generations, Israeli-Americans rarely maintain a unique identity. “We will not exist as Israeli-Americans 20 or 30 years from now,” Milstein said candidly in an interview with Jewish Journal.

To give Israeli-American young adults the chance to meet other young Jewish professionals, Milstein encourages participation in programs like B’Nai B’Rith. It’s a young professionals network designed to build community among working Israeli-Americans and American Jews ages 12 to 40. Milstein is practical; he understands that after three or four generations, Israeli-Americans rarely maintain a unique identity. “We will not exist as Israeli-Americans 20 or 30 years from now,” Milstein said candidly in an interview with Jewish Journal.

Through groups like B’Nai B’Rith, Milstein wants young Israeli-Americans to assimilate into the American Jewish community. However, he also wants them to take their Israeliness with them, including an unabashed pride in their homeland. In the future, Milstein hopes, “the Jewish people of America will be by us, and will not be the Jewish-Americans that you have today.” He believes Israeli-Americans have a duty to merge with the American Jewish community and focus its members on their connection with Israel.

For All Generations

The IAC’s flagship event, for the past few years, has been its Celebrate Israel festival. Instead of being age-specific like Milstein’s other programs, it brings together Israeli-Americans of all ages.

Celebrate Israel includes opportunities to eat Jewish food, listen to Jewish music, and enjoy traditional Jewish dances. It started in Los Angeles, but has since spread to several cities throughout the U.S., attracting thousands of enthusiastic participants.

At a recent Celebrate Israel festival in Pembroke Pines, Florida, attendees wandered through a replica of Jerusalem’s sprawling, bustling marketplace. They also had the chance to reflect while visiting a replica of Jerusalem’s Wailing Wall. Celebrate Israel isn’t just open to Israeli-Americans and American Jews; it welcomes Israel’s supporters from the wider community.

Unfortunately, it also attracts attention from groups that are inherently anti-Semitic. At Celebrate Israel’s New York event this year, the New Israel Fund, a BDS group, was allowed to march.

The New York Post spoke out strongly against the NIF and its presence at Celebrate Israel. “The Celebrate Israel Parade is a place for friends of Israel,” Ronn Torossian said in an editorial. “It should reject extremists of all kinds.”

The Ultimate Goal: Building Support for Israel

By launching a series of age-specific programs built around common Israeli-American interests, Adam Milstein has infused the Israeli-American community with new passion and cohesiveness. In a world environment increasingly hostile to the Jewish state, Milstein and his family work tirelessly to bring Jews and their allies together.

More than anything, Milstein believes that he and his fellow Israeli-Americans have a responsibility to promote Israel’s interests in America. “Israeli-Americans are knowledgeable and passionate about this subject,” Milstein wrote in an editorial for Jewish Journal. “They can speak from personal experience.”

When you look at the success of Silicon Valley, you see that most of it began at Stanford University. Starting with David Packard and William Hewlett’s little garage-founded electronic company in 1939, Stanford talent generated some of the Valley’s biggest successes, including Google and Cisco Systems. Every year,

When you look at the success of Silicon Valley, you see that most of it began at Stanford University. Starting with David Packard and William Hewlett’s little garage-founded electronic company in 1939, Stanford talent generated some of the Valley’s biggest successes, including Google and Cisco Systems. Every year,

In addition to being a force behind Campus Maccabees, the Milstein Family Foundation supports AIPAC’s Campus Allies Mission. The Campus Allies initiative offers non-Jewish, pro-Israel college students and young professionals the chance to visit Israel. For young adults with Judeo-Christian beliefs, a visit to the Holy Land provides a deeply spiritual experience.

In addition to being a force behind Campus Maccabees, the Milstein Family Foundation supports AIPAC’s Campus Allies Mission. The Campus Allies initiative offers non-Jewish, pro-Israel college students and young professionals the chance to visit Israel. For young adults with Judeo-Christian beliefs, a visit to the Holy Land provides a deeply spiritual experience.

For Jews raised in Israel, Jewish life operates on autopilot. The Jewish calendar governs all affairs, and all businesses close on Jewish holidays. Families share Jewish celebrations in schools, in public, and with one another.

For Jews raised in Israel, Jewish life operates on autopilot. The Jewish calendar governs all affairs, and all businesses close on Jewish holidays. Families share Jewish celebrations in schools, in public, and with one another. Another Sifriyat initiative pairs elementary school students with other people living in Israel. Using an online platform called Storyly, kids can

Another Sifriyat initiative pairs elementary school students with other people living in Israel. Using an online platform called Storyly, kids can

Today’s American Jewish community is a mix of Orthodox and non-Orthodox, a blend of multi-generation Americans and emigrants from modern-day Israel. A recent Pew Research release, for example, suggests that

Today’s American Jewish community is a mix of Orthodox and non-Orthodox, a blend of multi-generation Americans and emigrants from modern-day Israel. A recent Pew Research release, for example, suggests that  In November 2014, UCLA’s student council passed a resolution in support of the BDS movement. A few months later, when interviewing Jewish student Rachel Beyda for their Judicial Board, they asked whether her participation in Hillel and in Jewish sorority Sigma Alpha Epsilon Pi made it impossible for her to be “objective” when considering issues before the council. Four student council members voted against Beyda’s addition to the board in spite of her outstanding qualifications. They were concerned about whether Beyda’s

In November 2014, UCLA’s student council passed a resolution in support of the BDS movement. A few months later, when interviewing Jewish student Rachel Beyda for their Judicial Board, they asked whether her participation in Hillel and in Jewish sorority Sigma Alpha Epsilon Pi made it impossible for her to be “objective” when considering issues before the council. Four student council members voted against Beyda’s addition to the board in spite of her outstanding qualifications. They were concerned about whether Beyda’s  Celebrate Israel draws equal numbers of Israeli-Americans and American Jews. The Pembroke Pines festival featured a Mahane Yehuda Market designed to imitate the giant open market in downtown Jerusalem. It also featured a replica of the Wailing Wall, a deeply meaningful symbol even to non-practicing Jews.

Celebrate Israel draws equal numbers of Israeli-Americans and American Jews. The Pembroke Pines festival featured a Mahane Yehuda Market designed to imitate the giant open market in downtown Jerusalem. It also featured a replica of the Wailing Wall, a deeply meaningful symbol even to non-practicing Jews. In the turbulent Middle East, Israel has benefited greatly from its alliance with American allies. The U.S. has contributed a collective $121 billion to

In the turbulent Middle East, Israel has benefited greatly from its alliance with American allies. The U.S. has contributed a collective $121 billion to  In addition to supporting his own causes, Milstein works tirelessly to unite many Israeli-American and Jewish charities in common purpose. “Everything that I do, I put a few organizations together,” Milstein explains. “I make them work together, make them empower each other, and create a force multiplier.”

In addition to supporting his own causes, Milstein works tirelessly to unite many Israeli-American and Jewish charities in common purpose. “Everything that I do, I put a few organizations together,” Milstein explains. “I make them work together, make them empower each other, and create a force multiplier.” In the U.S., many left-leaning voters and young Americans equate being pro-Israel with supporting conservative evangelical candidates. Yet the

In the U.S., many left-leaning voters and young Americans equate being pro-Israel with supporting conservative evangelical candidates. Yet the

Adam Milstein

Adam Milstein The Adam and Gila Milstein Family Foundation founded the

The Adam and Gila Milstein Family Foundation founded the

The Adam and Gila Milstein Family Foundation supports a wide range of local charities in Los Angeles, including Bikur Cholim, a charity devoted to providing companionship and activities for the homebound, and Beit T’Shuvah, a residential facility for addiction treatment. Milstein also co-founded the Israeli-American Council and supports a number of on-campus groups, for Jewish and non-Jewish students alike, to build awareness about Israel and Middle East policy.

The Adam and Gila Milstein Family Foundation supports a wide range of local charities in Los Angeles, including Bikur Cholim, a charity devoted to providing companionship and activities for the homebound, and Beit T’Shuvah, a residential facility for addiction treatment. Milstein also co-founded the Israeli-American Council and supports a number of on-campus groups, for Jewish and non-Jewish students alike, to build awareness about Israel and Middle East policy.